Singular Value Decomposition

August 26, 2021 10 min read

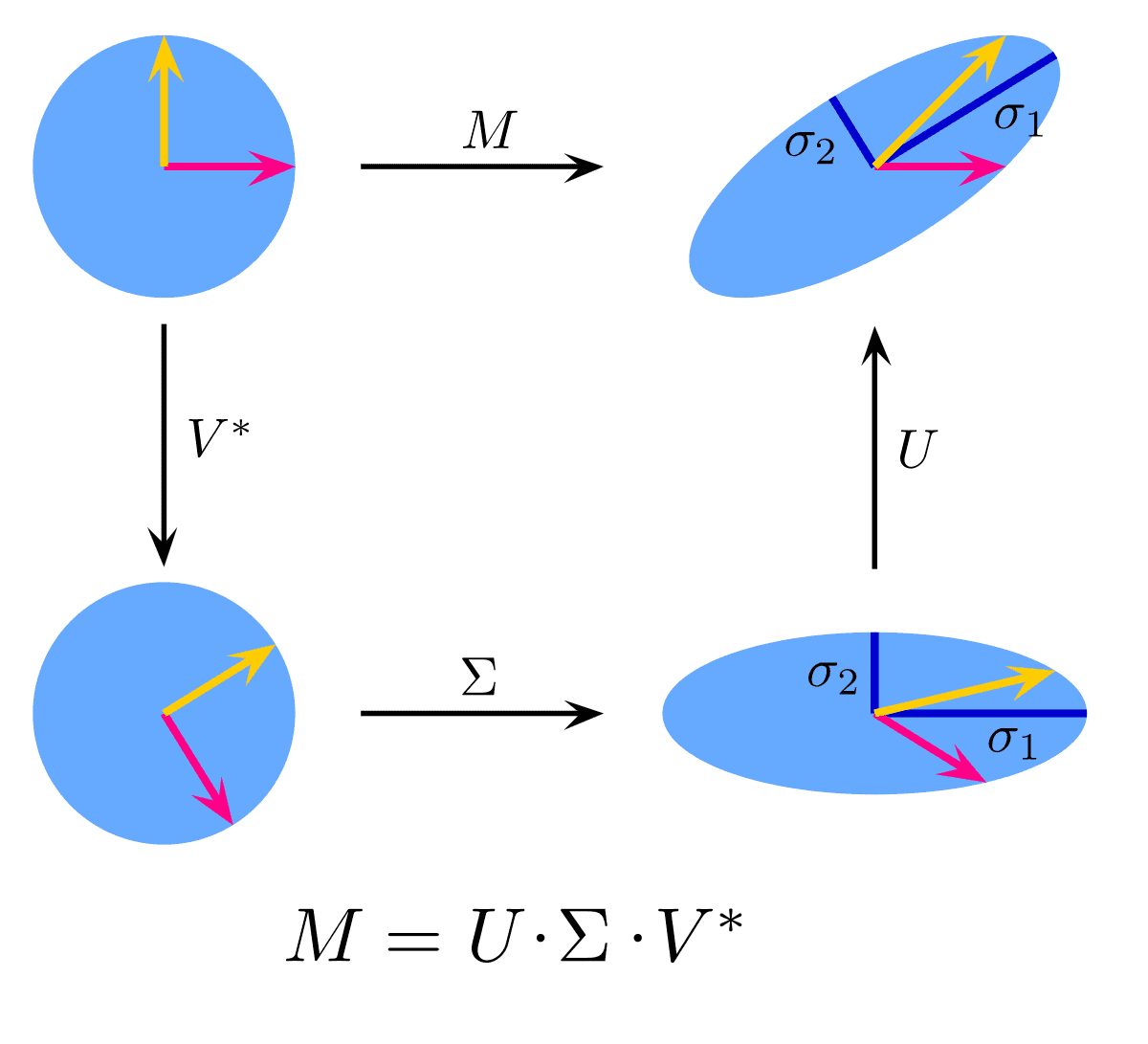

Singular value decomposition is a way of understanding a rectangular (i.e. not necessarily square) matrix from the operator norm standpoint. It is complementary perspective to eigenvalue decomposition that finds numerous application in statistics, machine learning, bioinformatics, quantum computers etc. This post explains its nature and connections to operator norm, least squares fitting, PCA, condition numbers, regularization problems etc.

Intuition for SVD from operator norm perspective

Suppose that you have a rectangular matrix , where its columns are people and each element of a column is how much they love horror movies and drama movies (I’m obviously drawing some inspiration from Netflix challenge).

Suppose that you are going to estimate the average fractions of your audience that prefer horror or drama movies. So you might be interested in multiplying this matrix by a vector of weights. For instance, if you are Netflix and 0.5 of your income is created by person 1, 0.2 - by person 2 and 0.3 - by person 3, your vector and is a 2-vector that reflects, what fractions of your total income horror movies and drama movies produce.

In the spirit of matrix/operator norms you might ask: if I applied this matrix to a vector of length 1, what is the largest length of vector I might receive on output?

The answer is simple: you need to calculate the following dot product (and then take square root of it to get the length):

As you can see, in the middle of this dot product we have a square 3-by-3 matrix , which is symmetric. That means that its eigenvectors are orthogonal/unitary. So we can represent it as an eigen decomposition: , where is an orthogonal matrix of eigenvectors.

Then the squared length of vector takes the form and the answer to our question becomes straightforward: the largest length of vector is achieved when x is the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue . The square roots of elements of matrix D of the eigenvectors of matrix , are known as singular values and denoted . We’ve already run into them previously, while exploring the condition numbers.

On the other hand, we can consider a matrix instead of . It is a 2-by-2 matrix, which, again, is symmetric. Again, it has orthogonal/unitary eigenvectors matrix, which we will denote .

Note that matrices and are known as Gram matrices. As we’ve seen above that each Gram matrix is a square of a vector length by design, Gram matrices are positive semi-definite and, thus, their eigenvalues are non-negative.

Left Gram matrix and right Gram matrix have identical eigenvalues

Consider a rectangular matrix . We can construct two different Gram matrices from it:

of dimensionality x and non-full rank 2

of dimensionality x and full rank 2.

However, both of these matrices have identical eigenvalues. It is surprisingly easy to see this.

Suppose that is an eigenvector of and is its corresponding eigenvalue:

Multiply both left and right sides of this expression by :

Now from this formula by definition the vector is an eigenvector for , and is the corresponding eigenvalue.

Hence, the eigenvalues are identical for and , and their eigenvectors are also connected (see next part).

Connection between left and right singular vectors

Here comes the key point of SVD: we can express vectors through . I will show how, but first take note that is a 2-vector, and is a 3-vector. Matrix U has only 2 eigenvalues, while the matrix v has 3. Thus, in this example every can be expressed through , but not the other way round.

Now let us show that , where are singular values of matrix . Indeed:

If we re-write in matrix form, we get:

or, equivalently, , or .

This proves that singular value decomposition exists if matrices and have eigenvalue decomposition.

Clarification of notation for eigenvalues matrix

Let us assume that we can always find a decomposition:

Then and:

In both cases of and this decomposition is consistent with properties of a Gram matrix being symmetric and positive-semidefinite: the eigenvectors of both matrices are orthogonal and eigenvalues are non-negative.

When I write note a notation abuse here: in reality we are multiplying rectangular matrices and resulting matrices are of different dimensionality. In we call a x matrix:

.

In we call a x matrix:

Matrix norms from singular values perspective

Nuclear norm and Schatten norm

In the condition numbers post we considered two kinds of matrix norms: operator norm and Frobenius norm.

In this post it would be appropriate to mention another family of norms: Schatten norms and their important special case, [Nuclear norm/Trace norm](Mirsky’s inequality)

Trace norm is awesome: if you take a rectangular matrix, apply L1 regularization to it, and apply a Trace lasso to it, you will effectively find low-rank approximations of your matrix, giving you a nice alternative to non-negative matrix approximation! See Trace Lasso paper. Hence, amazingly, the problems of sparse and low-rank approximations are interconnected.

Read more on affine rank minimization problem and sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems, if you find this topic interesting.

A new perspective on Frobenius norm

Singular values also provide another perspective on Frobenius norm: it is a square root of sum of squares of singular values:

To see this, consider a Gram matrix .

Obviously, the diagonal elements of Gram matrix are sums of squares of the rows of matrix .

Hence, the trace of Gram matrix equals to Frobenius norm of matrix . At the same time, as we know, trace of Gram matrix equals to the sum of eigenvalues of Gram matrix or sum of squares of singular values of the original matrix .

This fact, I believe, gives rise to an uncannily useful family of statements, called Weyl’s perturbation theorem or a similar Hoffman–Wielandt inequality for Hermitian matrices in matrix analysis. Both results are generalized by Mirsky’s inequality.

Informally speaking, they state that if two matrices differ in Frobenius norm by less than , their respective eigenvalues (also differ by less that . This theorem, for instance, lets us prove that eigenvalues of a Toeplitz matrix converge to the eigenvalues of a circulant matrix.

Operator/spectral norm

Matrix spectral norm is simply its largest singular value.

Application: low-rank matrix approximation

As we’ve seen singular values provide a convenient representation of a matrix as a sum of outer products of column and row-vectors (each outer product, thus, results in a matrix of rank 1):

Here’s the catch: as singular values are ordered in decreasing order, we can use SVD as a means of compression of our data.

If we take only a subset of first elements of our SVD sum, instead of the full elements, it is very likely that we would preserve most of the information, contained in our data, but represent it with only a limited number of eigenvectors. This feels very similar to Fourier series. This is also a reason, why PCA works (it is basically a special case of SVD).

References

- https://www.mat.tuhh.de/lehre/material/Regularisierung.pdf

- https://www.math3ma.com/blog/understanding-entanglement-with-svd

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gram_matrix

- https://gregorygundersen.com/blog/2018/12/20/svd-proof/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9vJDjkx825k

- https://personal.utdallas.edu/~m.vidyasagar/Fall-2015/6v80/CS-Notes.pdf - intro to compressed sensing

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1611.07777.pdf - Affine matrix rank minimization problem

- https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:900592/FULLTEXT01.pdf - a great thesis on dynamic systems sparse model discovery

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvbbXX8Bd90 - video on dynamic systems sparse model discovery

- https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-significance-of-the-nuclear-norm - references to the meaning of nuclear norm

- https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/192214/prove-that-xx-top-and-x-top-x-have-the-same-eigenvalues - identical eigenvalues of left and right Gram matrices

- https://www.arpapress.com/Volumes/Vol6Issue4/IJRRAS_6_4_02.pdf - Wielandt matrix and Weyl theorem

- https://case.edu/artsci/math/mwmeckes/matrix-analysis.pdf - matrix analysis (contains Hoffman-Wielandt inequality for Hermitian matrices)

Written by Boris Burkov who lives in Moscow, Russia, loves to take part in development of cutting-edge technologies, reflects on how the world works and admires the giants of the past. You can follow me in Telegram